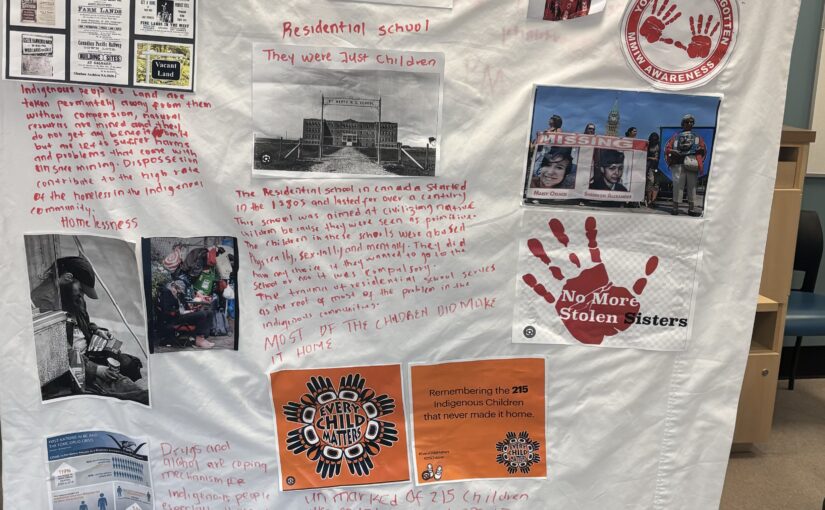

Visiting the residential school was one of my main experimental learning experiences, which helped me to better comprehend my Indigenous way of knowing class and indigenous peoples struggle in general.

It was a profoundly transforming journey that alters perspectives and imparts knowledge of Canada’s history as well as the struggles faced by its Indigenous population.

Prior to immgrating to this country my understanding of Canada was influenced by an idealized portrayal of a country that values diversity, inclusivity, and social harmony. But when I made my way through the eerie remains of residential schools, my entire comprehension was called into question. Preconceived ideas of a kind country were broken by the sharp reality of institutional injustices against Indigenous communities, which were replaced by knowledge of Canada’s difficult and complicated past.

In addition to being instructive, the visceral interactions in residential schools and talks with survivors are emotionally charged events that reshape one’s relationship to history. My own understanding is intertwined with the personal stories of survivors, which cultivates empathy and a strong feeling of accountability. The experiences go beyond scholarly understanding, causing one to reassess one’s own moral principles and the function of the writer in creating stories that aid in the healing of society.

I have a stronger commitment to ethical storytelling and a heightened social conscience as a result of these encounters. With a renewed knowledge of the writer’s role in amplifying minority voices and sensitively confronting past injustices, the art of writing becomes a potent instrument for advocacy and awareness. I quickly realize that telling stories is about more than just retelling the past; it’s also about adding to a common narrative that promotes understanding and peace.

It becomes clear how my preconceptions and the reality of Canada after immigration disagree. The difficulties faced by Indigenous people, who are frequently left out of mainstream narratives, are highlighted. Action and attention are required due to the harsh realities that these communities endure, including the intergenerational trauma resulting from residential schools and ongoing systemic issues. I am forced by this experiential learning to face the difficult realities and intricacies of the Canadian environment.

I use the experiences of Indigenous people as a prism to examine the larger sociopolitical environment. It makes me think about how I fit into this intricate story as an individual and how my work can help to break down prejudices and promote understanding. The persistent differences in the availability of healthcare, education, and employment prospects highlight how urgent systemic change is.

To sum up, taking an experiential learning course focused on social justice and human writing that revolves on residential schools and survivor gatherings can be a life-changing experience. It alters perceptions, increases empathy, and imparts a feeling of accountability. The contradiction between stereotypes and Canadian reality serves as a catalyst for campaigning and awareness-raising. Indigenous people’s hardships become more than just a historical backdrop; they also serve as a call to action for the present, highlighting the critical role that storytelling will play in fostering an inclusive and equitable future.

It also influenced my final project for settler colonialism decolonization and responsibility. MY CANADIAN DREAM VS MY CANADIAN REALITY